Science fiction, being entertainment rather than instruction, frequently traffics in setting and plot elements that have only a passing acquaintance with SCIENCE… and sometimes no acquaintance at all.

Some of this is due to authorial ignorance. Authors might have skipped any physics courses, know nothing about thermodynamics, and see nothing wrong with the notion that one can heat fuel to millions of degrees using only reflected light from a 5000 Kelvin source. Sometimes plot demands some authorial sleight of hand. If you need to get your characters from planet A to planet B faster than relativity would allow, you have to invent wormholes, FTL, teleportation, or some other kludge.

And sometimes, at least at one time, you had to ignore any scientific background you might have acquired in order to sell stories to John W. Campbell, Jr., editor of Astounding, later renamed Analog, a premier SF magazine of the 1940s through the 1960s.

Campbell had two virtues treasured by professional authors: his magazine paid comparatively well, and it paid without the need for lengthy lawsuits. He balanced these virtues with a stable full of hobbyhorses, each new hobby horse odder and less tethered to reality than the previous (see, for example, his defense of the scientifically impossible Dean drive). Incorporating one or another of Campbell’s pet concepts into one’s work appears to have greatly increased the likelihood that he would purchase a story. Which gets us to psionics in science fiction.

Campbell was by no means the first fervent believer in parapsychology. Efforts to research psychic phenomena go back at least as far as the 19th century. He wasn’t even the first person to incorporate psychic powers into SF. But he was the most prominent true believer who also happened to edit what was for quite some time the best paying, most influential post-Gernsbackian SF magazine early in SF’s history. He was therefore in a position to greatly amplify the frequency with which psychic powers (renamed “psionics” to sound more science-y) appeared in science fiction.

Noted critic William Atheling Jr.’s Practice Makes Perfect—But It Can Also Cut Your Throat (1957) observed that by one count “113 pages of the total editorial content of the January and February 1957 issues (of Astounding) are devoted to psi and 172 pages to non-psi material,” and by another, the same issues had “145 pages of psi text, and 140 pages of non-psi.” I’ll explain where the two sets of figures came from later.

Here are five classic SF stories crafted to appeal to Campbell’s quirks.

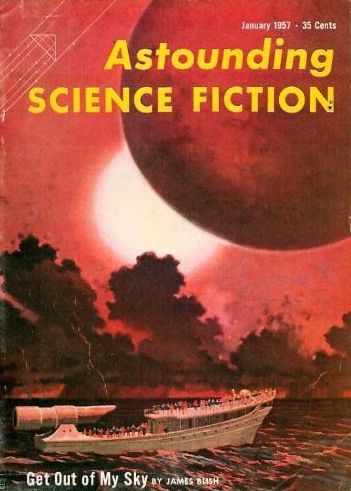

Get Out of My Sky by James Blish (1957)

(First appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, January 1957, and Astounding Science Fiction, February 1957)

Rathe and Home are Earthlike worlds that orbit each other, tide-locked just as the Moon is tide-locked to Earth. Land on Home is limited to the hemisphere antipodal to Rathe. Having belatedly explored their world ocean and so discovered Rathe’s existence, the people of Home are displeased by this unrequested addition to their sky. The fact that Rathe has natives makes Rathe even more abhorrent. This is the sort of problem H-bombs were designed to cure. The natives of Rathe, preferring to remain alive, turn to the powers of the mind to forestall doom.

Normally I’d review the five works on this list in dogged publication order, but I wanted to discuss this work first. It’s the very work that led William Atheling Jr. to equivocate about psi vs non-psi in the two issues of Astounding mentioned above. Get Out of My Sky’s first installment lacked psi but the overall plot depended on mind-powers. William Atheling Jr. had an unusually keen insight into Blish’s creative processes, as “William Atheling Jr.” was the penname under which James Blish published his SF criticism. And yes, Atheling did comment on Blish works. Not always favourably.

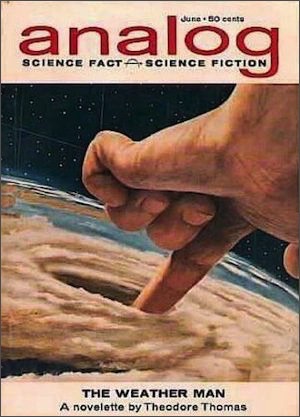

“Novice” by James H. Schmitz (1962)

(First appeared in Analog Science Fact & Fiction, June 1962, later incorporated into the fix-up The Universe Against Her)

Fifteen-year-old Telzey Amberdon’s visit to Jontarou provides her least-favourite aunt Halet with a pretext to persecute Telzey. Telzey’s beloved pet Tick-Tock being the only known living crest cat, Halet sets in motion the process to have Tick-Tock confiscated for the Life Banks (arguing that this would be for the greater good). There are just two flaws in this plan: Halet underestimates both Telzey and the crest cats, who are not extinct at all. Nor does Halet realize that an attack on Tick-Tock could threaten the lives of every human on the planet. Human survival will depend on Telzey’s ingenuity.

Telzey is very smart, has relatives highly placed in the government of the Federation of the Hub, and subscribes to ethics sufficiently pliable as to justify whatever action seems necessary to handle the crisis at hand. A seemingly endless suite of psionic powers hardly seems necessary to make this plot work. Nevertheless, Telzey possesses mental abilities that should make the most hardened foe think twice…and yet they never do. Of course, spiteful Halet had no idea that her that niece could re-write minds.

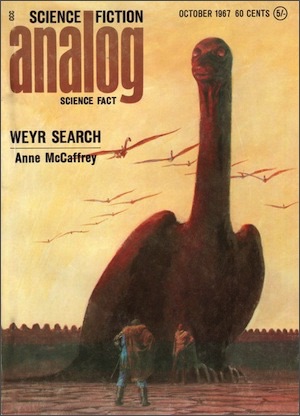

Weyr Search by Anne McCaffrey (1967)

(First appeared in Analog Science Fiction & Fact, October 1967, later incorporated into Dragonflight)

Pern is but one of many settled planets, one that has long been forgotten by the mainstream of galactic civilization. Periodic calamities overlooked at the time of settlement have reduced Pern to a patchwork of feudal holdings, such as the one cruel lord Fax took for his own. Young Lessa is determined to see Fax punished for overthrowing and murdering her family. Her taste for revenge blinds her to the greater destiny that fate has in store for her.

The people who settled Pern no doubt had many marvelous technologies, Due diligence before colonizing Pern was not one of them, which is why ravenous alien Thread falling from the sky came as a rude surprise. It’s fortunate that while the Pernese may be technologically backward, they and the pet dragons I probably should have mentioned earlier are armed with a wealth of mind-powers.

Pandering to Campbell could pay off on grander stages: McCaffrey’s tale was nominated for the Nebula, won a Hugo, and kicked off the long-running, popular Dragonrider series.

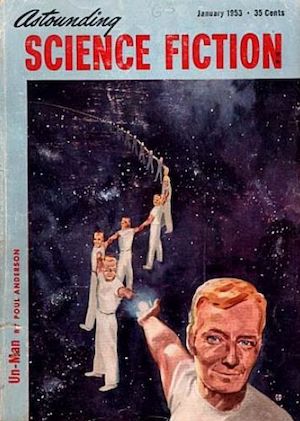

Un-Man by Poul Anderson (1953)

(First appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, January 1953)

The world barely survived World War Three. A world government is necessary to avoid World War Four. All right-thinking people therefore support the UN. Only blinkered nationalists oppose the UN, like the cabal who murdered UN agent Martin Donner. Among the nationalists’ many flaws: a foolish belief that killing Martin would confound the UN. Martin, you see, was simply one of many clones of man-of-action Stefan Rostomily. All the murder achieves is to earn the undivided attention of Martin’s clone-brother Robert Naysmith. Should Naysmith fall in his turn, there are legions of clones to replace him.

Anderson’s desire to sell to Campbell may have been balanced by his desire for scientific verisimilitude. Anderson’s tale offers one of the more notably mundane explanations for supposed telepathy that I’ve ever encountered: the alleged habit of most people to subvocalize their thoughts combined with exceptionally acute hearing.

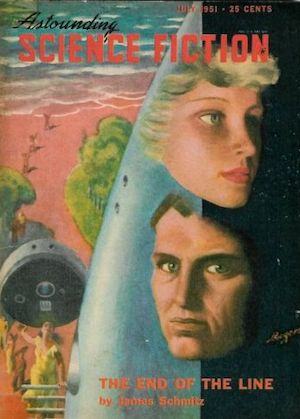

“The Greatest Invention” by Jack Williamson (1951)

(First appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, July 1951)

Human cultures across the galaxy credit fabled Atlantis as the garden from which civilization grew. Atlantis’ true location is a mystery, dozens of worlds each claiming they were the planet where Mankind began. One scientist has convinced himself that Atlantis must have been on Earth. His efforts to understand how such a backward world could have invented, then lost, interstellar flight blind him to a more pressing challenge: surviving the homicidal intentions of a companion determined to protect Truth from mere scientific fact.

Brevity would have been strength. This rambling tale does have some points of interest. Williamson takes the time to explain why all inhabitable worlds have ecologies in which humans could have evolved: successful colonization requires whole ecological networks to be introduced, rather than a single species of hopeful pioneers. More relevant to the purpose of this essay, this is said to be the story that coined the term “psionics,” which the story assures us is key to advanced civilization for reasons never made clear. Or, at least, it’s key for authors wishing to sell material to John W. Campbell, Jr.

***

These are hardly the only stories I could have cited. Perhaps you have your own favourite examples of stories meticulously shaped around the very special mental powers that Campbell loved, or others where the author clearly just crammed them in in a bid to get that wonderful check from Astounding/Analog. If so, comments are, as ever, below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021 and 2022 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.